Why do we like to play games?

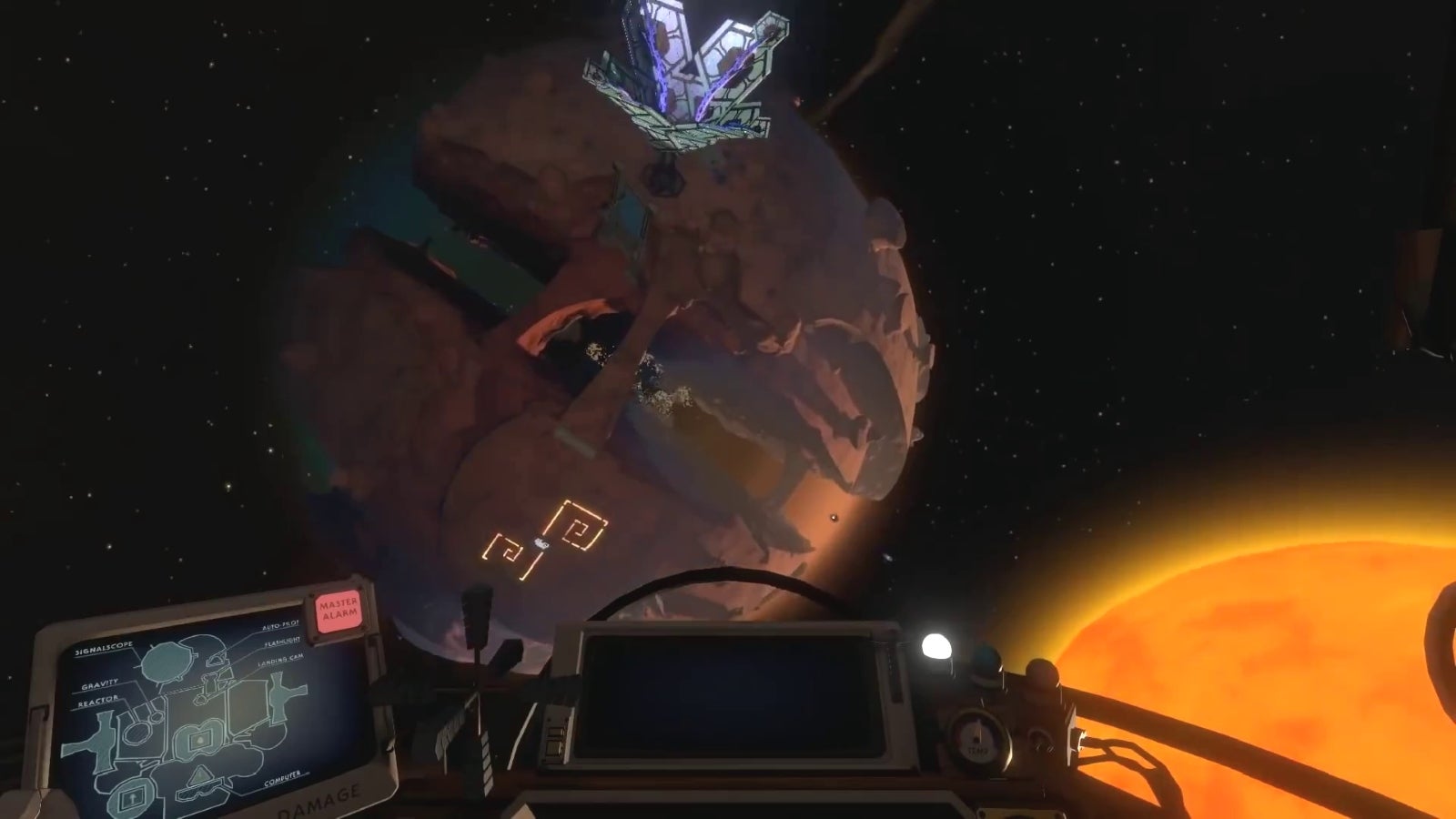

Outer Wilds is an indie puzzle-based exploration game developed by Mobius Digital set in a minituarized solar system where spacefaring players travel to discover its secrets and uncover the remains of an ancient alien race – all within a 22 minute time loop. An initial version of the game was an entrant in IGF 2015 before being fully released on PC, Xbox One and PS4 on May 2019.

Think back to when you first picked up a controller, what was it about gaming that drew you in? Was it the depth of the game mechanics, the interwoven emergent gameplay systems, or the immense eye-candy on screen meant to short-circuit your dopamine receptors? I wager it was none of these, instead it was the simple joy of exploring a completely unknown world and having your imagination spurred – in essence, the satiation of your human instinct for curiosity and discovery.

This post will analyze how Outer Wilds achieves a fulfilling player experience purely by using the player’s own curiosity and need for discovery by relating the game’s systems and design decisions to the Lenses of the Elemental Tetrad and Curiosity, Motivation, Problem Solving, Time, and Secrets.

The Elemental Tetrad

Aesthetics

The first real draw for any player to this game would be the almost surrealist solar system of Outer Wilds full of its wacky planets all drawn in a flat-shaded style that’s easy on the eyes. There’s just something about the allure of space that made us all want to be astronauts at some point in our childhood. Naturally, this allure feeds directly into the curiosity a player has about this game and its world, and serves to strengthen the game’s core premise of exploration driven by player motivation.

Technology & Mechanics

An exploration game set in a solar system would in no way be complete without a depiction of the larger-than-life forces at play around some massive celestial bodies. Outer Wilds in fact performs a fairly accurate physics simulation of a solar system within the Unity game engine, with each planet in its own orbit around the sun, and the varied effects of gravity experienced around and on different planets.

The core mechanics of flying a spaceship and navigating the surface of different planets in the game directly play off the physics technology behind Outer Wild’s solar system. This creates a surprisingly challenging and thereby engaging second-to-second player experience as the player needs to always consider their movement in 6-axis and how slight differences in gravity around the solar system can offset their entire mental positioning model.

Despite the game’s humble aesthetics, these deep movement mechanics and accurate physics simulation add a sense of believability into the world that serves to sufficiently suspend the player’s disbelief to prime them for the last aspect of the Elemental Tetrad:

Story

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18321987/Outer_Wilds_The_Attlerock__0000_Layer_8.jpg)

The story of Outer Wilds is almost entirely delivered through what are essentially text logs. There are no cutscenes, no audible dialog, and no deep dialog trees or other interaction systems. With such a bare bones method of storytelling, one would assume that the game would be nothing short of a boring walking simulator.

However, the game’s text is specifically written to be engaging and spur the player’s curiosity about the solar system. Every piece of discovered text in the game has hints about locations, objects, or even characters hidden throughout the solar system. By serving as the player’s only guide to solving the game’s puzzles, players are in fact trained to be on the active hunt for these bits of lore instead of treating them as optional skippable collectibles.

This creates a feedback loop of curiosity that encourages the player to explore more to discover more lore, which in turn leads the player to even further discoveries and findings.

The Lens of Curiosity

There are absolutely no map markers in Outer Wilds. There is no sequential way players must visit each of the planets. There are no expectations the game puts on the player and on how they wish to experience the game. Then how is a player expected to know what to do next in an entire solar system?

This is where one of the key design decisions of the game comes in: designing planets, structures, etc. to be only as large as they need to be. Planets are barely the size of small real-world asteroids and most structures on a planet can be seen towering over the curvature of the planet from many kilometeres away in space.

These clearly designated zones make it very easy for players to spot something that piques their curiosity and to simply jump in their spaceship and travel there. Once a player sees how low the barriers to satisfying their curiosity are, they get even more curious since they no longer see invisible barriers, level-capped dungeons, or the other limitations that AAA games can have on exploration, but instead the possibilities of going anywhere their heart desires.

The Lens of Motivation

Having the player realize that where they go and what they do in this solar system is only limited by their appetite for adventure allows the player to develop the previously discussed curiosity and need for discovery – one of the purest forms of motivation one can have for any aspect of life, let alone a game.

This free-form approach to player motivation coupled with the varied environments interestingly keeps the player engaged for much longer – since a player’s appetite for exploration could vary greatly based on their mood. The player does not have to explore the furthest, lonelinest reaches of the solar system if they just want to do something comfortable – and the game’s small yet dense world design allows for the player to experience progression in the story no matter where they are in the solar system.

The Lens of Problem Solving

Many puzzle games are based around the mastery of one or two mechanics to solve their puzzles, often building on top of these mechanics for more complex puzzles. Puzzle games that come to mind include Portal, The Witness, Monument Valley, etc.

Outer Wilds is unique in that there is no real mastery of a mechanic required to beat its puzzles. What the game requires mastery of instead, is knowledge itself. To illustrate, a player who has understood the rules of the solar system can finish the game within the very first time loop itself – no exploration required.

This knowledge encompasses multiple instances of knowing where to go, when to go there, and what to do there – all in the right order – all leading up to the finale of the game. This is where the game achieves extreme cohesion in design as the aesthetics, story, the player motivation, and their curiosity all come together to ensure the player is always acquiring new knowledge about the solar system, and slowly pieceing together its many secrets.

The Lens of Secrets

Outer Wilds does not hide its best secrets. They are almost always in plain sight right in front of the player, waiting till the player acquires the knowledge to see the secrets for what they are. This creates numerous Eureka! moments throughout the game that give the players more incentives for exploration and to stay curious.

A slight spoiler of an example:

On one of the planets, underground caves are continually being filled up with sand throughout the time loop. Thus being stuck in a cave while the sand fills around you spells imminent death. There is a particular room thats needs to be accessed at the end of a long cavern, but it always seems like there is never enough time to get to the entrance before the sand crushes you. However, if a persistent player explores enough, the rising sand outside the narrower cavern will eventually lead you to an opening on the surface of the planet that allows for a much quicker entrance into the cave system, thereby giving you enough time to reach the locked room.

The Lens of Time & A Fitting Conclusion

All things come to an end. Appropriately then, in the end of this blog post, we discuss a final masterstroke in Outer Wild’s design – the game’s 22-minute time loop that ends with the solar system burning up in a supernova and the player losing all their progress.

While this undoing of progress might seem initially frustrating, the 22-minute time loop plays favourably into Outer Wilds’ strengths. Firstly, the time loop incentivizes the player to optimize their playthrough towards exploration and gathering knowledge – one of the game’s design goals. The duration of the time loop is also extremely well balanced such that the player has only enough time to satisfy one or two of their curiosities, leaving behind the rest of their unanswered questions for subsequent time loops. This ensures that there is always a list of things that the player wants to try in their next loop, hooking them to the game and making them constantly curious to keep exploring.

To conclude, almost every design decision in Outer Wilds – ranging from the creation of intrinsic curiosity and motivation, the dense, hand-crafted solar system, and the knowledge-based progression system – coalesces to answer the question of why we started playing games in the first place: to explore, to discover, and to get lost. To this end, I believe Outer Wilds is as pure as a game can get, and must be experienced at least once by anyone who has become disillusioned with AAA and mobile gaming.

![Don't Starve Winter Guide [+ Mods] | DS & DST - Basically Average](https://basicallyaverage.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/14184511/wilson-winter-fire-pit-drying-rack-science-machine.jpg)