Summary

Celeste is a widely popular indie game centred around themes of depression, anxiety, mental health and self-realisation. In it, the player controls a young girl named Madeline, who tries to climb Celeste Mountain while facing the challenges that arise from the natural landscape and from her own fractured sense of identity.

The Elemental Tetrad

Mechanics and Technology

The core gameplay loop of Celeste is based around a series of successively more difficult platforming “rooms” that make up bigger chapters, carrying along the story as the player moves higher and higher up Celeste Mountain. One of Celeste’s most endearing features is its simplicity of controls and mechanics. The player only has three main movement options: the jump, the dash (a sudden burst of speed in a chosen direction) and the wall climb. Crucially, the player refreshes their dash every time they hit the ground, and are only allowed to cling to a wall for a short duration before they lose stamina and fall. The limited chances to use the dash force the player to strategize appropriately across a room: using momentum to launch yourself across a large gap, stalling in the air with a dash to just get enough horizontal coverage, and nearly frame-perfect dashes in a particular direction are all elements Celeste demands mastery of in order to climb through its chapters.

Celeste doesn’t throw all of this at you at once, though, instead opting to introduce techniques progressively and building upon everything the player has learned to make them better and better at the game. This is the reason speedrunners the world over adore Celeste: playing the game makes you better at the game. After finishing the final level in the main story, any average player could go back to the start and find themselves remarkably faster, better and using advanced techniques with ease. Certainly, the levels are hard, but never to the extent of frustration. Instead, the quick respawn animation and emphasis on improvement over speed or death count gives the player an intrinsic motivation to keep going until they finally clear a tricky room or sequence.

Aesthetics

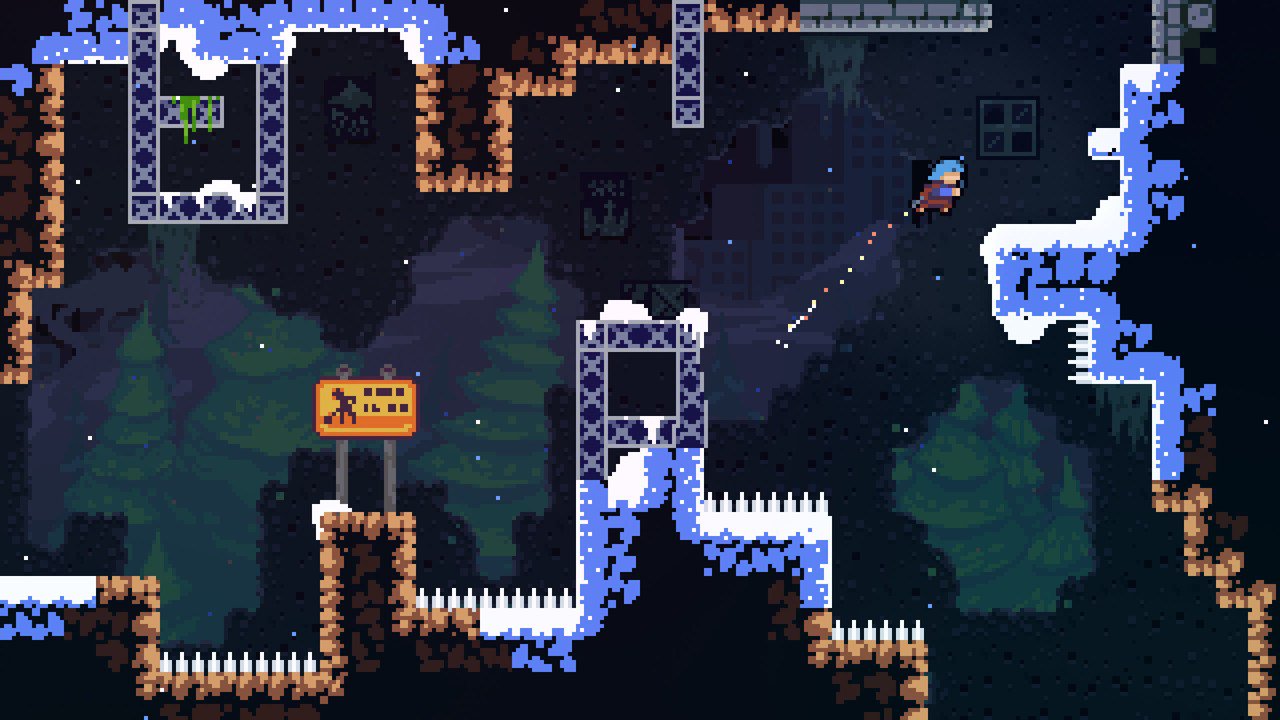

If the gameplay loop is what draws the player in, the aesthetics keep them hooked. The 8-bit, minimalist artwork of Celeste is captivating and perfectly gels with the game’s tone and gameplay style. The screen rumbles when you boost, the respawn animation zooms in on the death point and fades out the entire screen, only to put you back in almost immediately. Each chapter has its own unique art style, and the background reflects the journey Madeline is taking up the mountain. Where the game truly shines and comes into its own, though, is the soundtrack. Each track feels like it was crafted for its level from scratch, and the 8-bit synth feels very natural within the setting. Both elements come together to create a thoroughly immersive, transformative and endearing experience, that not only lets you control Madeline, but truly become her and empathise with her journey through the course of the game. Perhaps this is why so many regard clearing Celeste’s toughest challenges as badges of honour: there is a deep empathy to the journey of the game as it relates to the journey of the player.

Story

Celeste has a simple story at heart: a young girl climbs up a mountain while battling her self-doubt, anxiety and depression. From Granny’s mocking to the physical embodiment of Madeline’s dark side, the game portrays Madeline’s internal conflict through subliminal aesthetic messaging as well as astute storytelling and dialogue. Most importantly, however, is the idea of getting used to failing again and again just to get better (which the game encourages!), while using Madeline’s growing strengths and realisations. The game deftly ties together Madeline’s personal growth with her in-game movement options to lead the player on a parallel journey of personal improvement as well: one of patience and mastery of a craft. It’s not about defeating the voice in your head, says the game, it’s about working together with it. With a broadly appealing message and a subtly woven message about mental health underneath, Celeste uses simplicity of design and game design to drive home its key messages.

Lenses

The Lens of Accessibility

At its core, clearing Celeste’s rooms is a puzzle. From the very first bunny hops across a collapsing bridge to the final mid-air dashes off a moving platform, Celeste introduces progressively harder puzzles. The puzzles are structured as a means to mastery and intended as a labour of love. Try your first idea, see if it works, find an idea that is feasible, get the inputs perfect, and execute it. Rinse and repeat. Where Celeste finds its niche, however, is its Assist Mode. It offers a huge variety of assist options (additional dashes, slowing down the game, invincibility, etc.), and allows you to tune the degree of each of them that is enabled. The result is possibly the most accessible platformer ever created, with something for every possible player. On the other side are the challenge levels (B and C sides) and golden strawberries, which amp up the difficulty immensely and offer more content and challenge for those that desire it.

The Lens of Obstacle

Celeste is tough. There’s no two ways about it. From the platforming challenges to the pursuit levels to the weaving between rows of spikes as a golden feather, it requires the player to be on top of their game to clear each room. The obstacles are presented both by the landscape itself, and from within Madeline’s mind. As the terrain gets more challenging and Madeline confronts more of her intrusive thoughts, the platforming becomes tougher. It feels like you’re fighting not just against the mountain, but against Madeline’s internal conflict as well. The difficulty represents the mountain, the journey of the player, as well as Madeline’s own struggles. It all comes to a crescendo at the peak, where Madeline finally embraces the supposedly evil Part of Her and uses their combined powers to get to the top.

The Lens of the Avatar

Madeline has wide empathetic appeal. She’s young, struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts, and wants to show herself and the world what she’s capable of. It’s a premise most young people today find themselves in often. The approach the game presents to overcoming these issues, however, is non-intuitive: embrace every part of you and let go of what you can’t control. It’s an abstract thought that’s difficult to fully appreciate when conveyed verbally, but when presented through the metaphor of climbing a mountain, it sinks in. As the player overcomes platforming challenges and witnesses Madeline struggling with her own issues, there’s a deep empathy that arises from the parallel struggles. In this way, the game not only provides a meaningful and challenging experience, but conveys important lessons about approaching your own anxiety and dealing with mental health.

The Lens of the Toy

At the end of the day, Celeste is a game. From the moment you’re dropped into it, Celeste gives you no clues. You figure out how to move, and you figure out how to jump. Sure, the game gives you the basic controls (dashing, clinging to the wall, etc.), but whenever additional mechanics are introduced (spikes, moving platforms, launch bubbles, etc.) you’re largely left to poke them and see what they do. The game prioritises player exploration, and encourages the player to figure out the way they want to approach and solve each room. In a way, it’s like fitting Play-Doh into a shaped mould. There is an obvious way to solve the puzzle: mould it exactly. But you could also take a shortcut: tear it into two pieces and drop them in. The game never boxes the player in with rules or arrows pointing where to go: you are free to explore the branching paths and get the strawberries if you want to. You play at your pace, the way you want to.